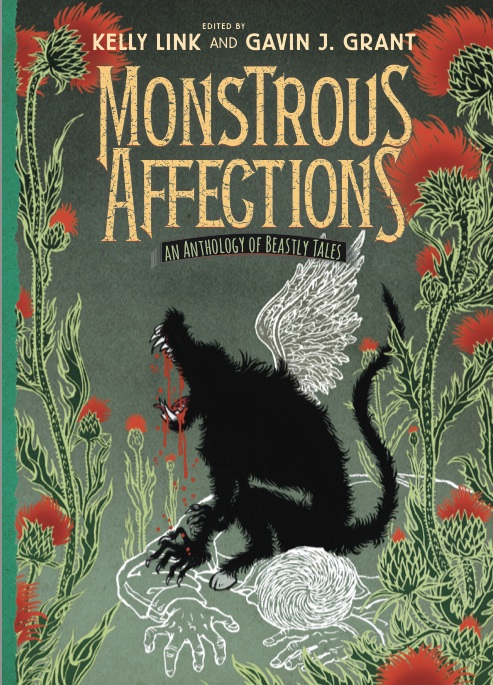

Monstrous Affections: An Anthology of Beastly Tales is an original anthology edited by Kelly Link and Gavin J. Grant, containing over four-hundred pages of stories—some dark, some silly, some intense—that approach the theme of the “monster” from a variety of angles. It’s a hefty tome featuring popular names like Paolo Bacigalupi, Nathan Ballingrud, Holly Black, Nalo Hopkinson, Alice Sola Kim and more, as well as several folks who are fresh to me. It’s even got one short graphic story by Kathleen Jennings.

Link and Grant are a dynamic and talented editorial pair—their press, Small Beer, publishes books I love with a statistically significant success rate; their previous anthology work is also strong—and Monstrous Affections is a solid addition to their oeuvre. It’s equal parts playful and sharp-edged, fooling around with tropes and clichés here while weaving disturbing and intimate fictions there. And as a part of a conversation on the generic conventions of “young adult” fiction, this is also a fascinating text—in part a challenge, in part a celebration.

Monstrous Affections, as it so happens, falls on an interesting genre “boundary”—that odd marketing space between young adult (by which I mean teenage) and young adult (those cusp years between eighteen and twenty-something), wherein the content is sometimes-though-not-always darker and more mature. It’s a space I find increasingly intriguing as more books become available that are marketed towards or seem to fall into it. Monstrous Affections is published by a press that handles primarily texts aimed at younger markets—Candlewick—but the content slips between stories I would consider “typically” young adult and those that might be intended for an older audience.

Which is of course a little silly to make a point of, when I think about it, because god knows fourteen-year-old-me was reading some raunchy, scary, weird stuff and I didn’t give a damn about categories. But the boundaries within which a book is placed on publication continue to interest current-me, nonetheless—whether or not they actually map onto the reading habit of real teens and no-longer-teens. In this case, the generic space is interesting because it also places these stories as part of a debate: they’re commenting on other pieces in the genre, exploring ways of telling stories that fit (or don’t) the accepted forms and structures YA stories tend to fall within.

So, Monstrous Affections, put simply: it is a young adult book (defined broadly), and it addresses the idea or concept of “monstrousness” from various and sundry angles—a theme anthology. And, in both categories, it works well. I don’t think it’s much of a stretch to call it one of the best young adult anthologies I’ve had the pleasure of reading, certainly, and there’s none of the staleness that I sometimes associate with too-narrow themes for collections.

There are far too many stories here to tackle them all individually, but I’d like to note a few stellar contributions: first off, the introduction, which is probably the strongest and most amusing editorial bit I’ve ever read. Honestly, even for a fellow-editor who feels a certain pressure to appreciate them, introductions tend to be a little blasé—but Link and Grant’s clever, silly introduction is a worthwhile read in and of itself. (I particularly like the personality quiz at the end: again, playing with genre tropes can be so appealing sometimes.)

As for stories, “Quick Hill” by M. T. Anderson is a long one—perhaps a novelette?—that takes place during a slightly alternate-universe World War II. It’s atmospheric, upsetting, and besides dealing with nominal teenagers is one of the pieces that I think would be at home in any adult anthology as well. The gender dynamics and understated presence of the uncanny, the supernatural, are all fascinatingly rendered in broad but delicate strokes. There’s a real sense of loss—loss of innocence, of safety, of belief—that permeates the last third, as well, which I found compelling. Strong stuff, though the pacing is a bit odd: it’s very much front-loaded as a narrative.

In contrast, Sarah Rees Brennan’s “Wings in the Morning” is as much a young adult story—in tone and trope—as anything in the entire anthology: it’s got a threesome of close friends, two young men and a young woman, it’s got coming of age and self-discovery, it’s got misunderstandings in love, and it’s got a happy ending. But (and here’s what I liked about it) it’s also got a truly and wickedly fun irreverence for other tropes: the young woman comes from a culture where the gender roles are effectively a reverse of contemporary Western ideals (men are soft emotional flowers, etc), the boys aren’t in love with her but (after mishaps and misunderstandings of course) each other, and the violence of war isn’t brushed under the rug for the fun of romance. The clever little reversals and the clear delight Brennan takes in writing within these generic structures make it a good read for me, though in a totally different way than the Anderson. More or less, it’s fun.

Kelly Link also has a story in this anthology, “The New Boyfriend,” that I was slow to warm up to initially but ended up appreciating. It takes the idea of the android-companion and mashes it up with girls’ cultural love for hot supernatural boys, which didn’t quite win my initial interest. However, the attention to the complexities of female friendship, love, and desire that Link ends up exploring through her protagonist’s weird affair with the haunted “Ghost Boyfriend” her rich best friend has… that’s right up my alley. As always, too, Link’s prose is handsome and engaging. It’s a light piece, in some ways—nobody’s going to be dismembered or anything, here—but it’s also intimate and serious in a pleasantly mundane way.

Lastly, Alice Sola Kim’s “Mothers, Lock Up Your Daughters Because They Are Terrifying” is a disturbing piece about four young women—all Korean adoptees—who accidentally summon up a “mother” to fill their perceived gap or loss of their birth mothers. It does not turns out well. This is another piece that could easily shift genre boundaries to a different kind of anthology; while it’s about teenage girls and their relations to each other and their families, as well as issues of race and identification, it’s also just remarkably dark and upsetting in the end. As an ending note, too, it’s a strong play; there’s definitely a visual and emotional resonance that carries over after one finishes reading it.

Overall, I found Monstrous Affections to be a pleasant and consistent read that—despite its size—never felt as if it were too long or too one-note. For a theme anthology at this length, that’s impressive; I likely shouldn’t be surprised, considering the editors in question, but I was delighted and relieved to find myself having no trouble at all devouring this book from cover to cover. While the variation inherent here means that some stories will appeal more to one reader than another—nature of the beast—I found that the strength of the general organization and the skill of the writers included made for a well-balanced and engaging collection. I’d definitely recommend giving it a look.

![]() Monstrous Affections: An Anthology of Beastly Tales is available now from Candlewick Press.

Monstrous Affections: An Anthology of Beastly Tales is available now from Candlewick Press.

Get a better look at Yuko Shimizu’s cover art for the anthology here on Tor.com. And check out our Pop Quiz interviews with Monstrous Affections’ editors, Kelly Link and Gavin Grant, as well as contributors Kathleen Jennings, Nik Houser, and G. Carl Purcell.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.